La Flor de Lis by Elena Poniatowska (1988).

La Flor de Lis by Elena Poniatowska (1988).

Appreciation ofElena Poniatowska’s La Flor de Lis by Sandra Cisneros

The little hand serving me coffee is also the hand that wrote the exquisite novel La Flor de Lis (1988). It seems absurd a writer of such worth should bother serving coffee to anyone, but it’s precisely this humility, this willingness to serve others, whether it be coffee, or novels, or testimonies, or tamales, that makes Elena Poniatowska a writer as well loved by cab drivers as by professors. The title alludes to France, but if you’re hip to Mexico City, you’ll know La Flor de Lis is also the famous tamale restaurant in la colonia Condesa.

"La Flor de Lis" is a love story about mother and motherland, about love of México lindo y querido (pretty and best), a culture where mothers are revered as goddesses, and a goddess, la Virgen de Guadalupe, is revered because she is “the” mother.

It’s a fairy tale told in reverse. Daughters of royalty flee France under siege from World War Il, and in the course of their childhood and adolescence in Mexico, we witness the discovery of what it means to belong to a culture, what it means to fall in love, and what, after all, it means to be a woman, because the story is steeped in the body of a woman, in the body of that country.

Nowhere else have I read anyone describe the joy of scrubbing a courtyard with a bucket of suds and a broom. But it’s el zócalo, the central plaza of Mexico City that the narrator wants to scrub out of puro amor. And that ultimately sums up how a writer like Elenita became Elena Poniatowska. What we do for love, after all, is the greatest work we can do.

Total Points: 5 (SC 5)

Hombre by Elmore Leonard (1961). Displaying his trademark ability to turn pulp into art, Leonard elevates the classic Western through the story of John Russell, a white man raised partly by Apache Indians who taught him how to fight and survive. The action begins when Russell boards a stagecoach and is rejected by passengers because of his roots. When outlaws pounce, the others turn to him for protection. Will he or won’t he? Leonard answers that question in this action-filled tale while probing Western myths, issues of race, and our responsibilities to our unlikable fellow man.

La Flor de Lis

La Flor de Lis Mildred Pierce

Mildred Pierce Of a Fire on the Moon

Of a Fire on the Moon On the Eve

On the Eve Pearl

Pearl Play It as It Lays

Play It as It Lays Red Shift

Red Shift Right Ho, Jeeves

Right Ho, Jeeves The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay

The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay The Betrothed

The Betrothed The Chateau

The Chateau The Complete Aubrey/Maturin novels

The Complete Aubrey/Maturin novels The Count of Monte Cristo

The Count of Monte Cristo The Custom of the Country

The Custom of the Country The Europeans

The Europeans The Folded Leaf

The Folded Leaf The Life of Pi

The Life of Pi The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

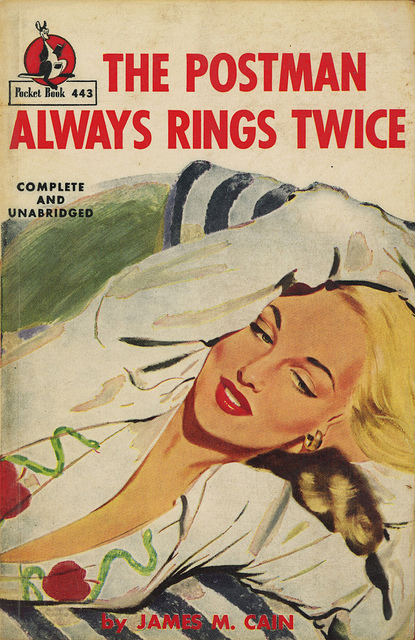

The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock The Postman Always Rings Twice

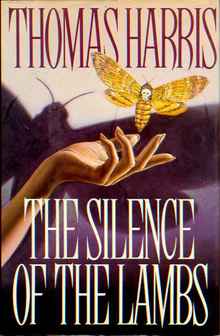

The Postman Always Rings Twice The Silence of the Lambs

The Silence of the Lambs