Author Photo And Bio

1. The Duel by Anton Chekhov (1891).

1. The Duel by Anton Chekhov (1891).

2. 1984 by George Orwell (1948). Orwell’s reputation as an antiauthoritarian arises in large part from this novel set in a totalitarian future in which citizens are constantly reminded “Big Brother is watching” as they are spied upon by the Thought Police and one another. In this landscape, Winston Smith is a man in danger simply because his memory works. He understands that the Party’s total control of its citizens is based on its ability to control its message and its citizens’ memories, and he is slowly drawn into a dangerous love affair and then an alliance, called the Brotherhood, of men and women united to fight Big Brother. Some of the vocabulary Orwell created for 1984—newspeak, doublethink, Big Brother—have become part of today’s vocabulary.

2. 1984 by George Orwell (1948). Orwell’s reputation as an antiauthoritarian arises in large part from this novel set in a totalitarian future in which citizens are constantly reminded “Big Brother is watching” as they are spied upon by the Thought Police and one another. In this landscape, Winston Smith is a man in danger simply because his memory works. He understands that the Party’s total control of its citizens is based on its ability to control its message and its citizens’ memories, and he is slowly drawn into a dangerous love affair and then an alliance, called the Brotherhood, of men and women united to fight Big Brother. Some of the vocabulary Orwell created for 1984—newspeak, doublethink, Big Brother—have become part of today’s vocabulary.

3. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899). In a novella with prose as lush and brooding as its jungle setting, Phillip Marlowe travels to the Belgian Congo to pilot a trading company’s steamship. There he witnesses the brutality of colonial exploitation, epitomized by Kurtz, an enigmatic white ivory trader. To understand evil, Marlowe seeks out Kurtz, whom he finds amongst the natives, dying. After Kurtz laments his own depravity through his final, anguished words—“The horror! The horror!”—Marlowe must decide what to tell his widow back home.

3. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad (1899). In a novella with prose as lush and brooding as its jungle setting, Phillip Marlowe travels to the Belgian Congo to pilot a trading company’s steamship. There he witnesses the brutality of colonial exploitation, epitomized by Kurtz, an enigmatic white ivory trader. To understand evil, Marlowe seeks out Kurtz, whom he finds amongst the natives, dying. After Kurtz laments his own depravity through his final, anguished words—“The horror! The horror!”—Marlowe must decide what to tell his widow back home.

4. Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (1811). Austen doubled her heroines here, giving us the down-on-their-luck Dashwood sisters. Elinor, the cool-headed elder, seems to embody common sense, while Marianne is “eager in everything.” The novel’s joy comes from watching the girls shape-shift their way through their love troubles, trading back and forth between their roles and natures. As each girl is by turns hardheaded and hot-hearted, Austen’s novel reveals the fluid nature of identity.

4. Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (1811). Austen doubled her heroines here, giving us the down-on-their-luck Dashwood sisters. Elinor, the cool-headed elder, seems to embody common sense, while Marianne is “eager in everything.” The novel’s joy comes from watching the girls shape-shift their way through their love troubles, trading back and forth between their roles and natures. As each girl is by turns hardheaded and hot-hearted, Austen’s novel reveals the fluid nature of identity.

5. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (1966). Bulgakov reshaped his experience of Stalinist censorship into a surreal fable featuring three characters: an unnamed author (the Master) whose accusatory fiction is denied publication, his self-sacrificing married lover (Margarita), and the incarnation of Satan (Woland), who simultaneously orchestrates and interprets their destinies. The ambiguity of good and evil is hotly debated and amusingly dramatized in this complex satirical novel about the threats to art in an inimical material world and its paradoxical survival (symbolized by the climactic assertion that “manuscripts don’t burn”).

5. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (1966). Bulgakov reshaped his experience of Stalinist censorship into a surreal fable featuring three characters: an unnamed author (the Master) whose accusatory fiction is denied publication, his self-sacrificing married lover (Margarita), and the incarnation of Satan (Woland), who simultaneously orchestrates and interprets their destinies. The ambiguity of good and evil is hotly debated and amusingly dramatized in this complex satirical novel about the threats to art in an inimical material world and its paradoxical survival (symbolized by the climactic assertion that “manuscripts don’t burn”).

6. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930). The Bundrens of Yoknapatawpha County have a simple task—to transport their mother’s body by wagon to her birthplace for burial. Faulkner confronts them with challenges of near biblical proportions in this modernist epic that uses fifteen different psychologically complex first-person narrators (including the dead mother) through its fifty-nine chapters. Soaring language contrasts with the gritty sense of doom in this novel that includes the most famous short chapter in literature: “My mother is a fish.”

6. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930). The Bundrens of Yoknapatawpha County have a simple task—to transport their mother’s body by wagon to her birthplace for burial. Faulkner confronts them with challenges of near biblical proportions in this modernist epic that uses fifteen different psychologically complex first-person narrators (including the dead mother) through its fifty-nine chapters. Soaring language contrasts with the gritty sense of doom in this novel that includes the most famous short chapter in literature: “My mother is a fish.”

7. Tom Jones by Henry Fielding (1749). Squire Allworthy provides a loving home to his bad nephew Blifil and the bastard orphan Tom. Lusty Tom is sent away after an affair with a local girl whom Blifil desires, and he begins his picaresque adventures on the way to London, including love affairs, duels, and imprisonment. Comic, ribald, and highly entertaining, Tom Jones reminds us just how rowdy the eighteenth century got before the nineteenth came and stopped the fun.

7. Tom Jones by Henry Fielding (1749). Squire Allworthy provides a loving home to his bad nephew Blifil and the bastard orphan Tom. Lusty Tom is sent away after an affair with a local girl whom Blifil desires, and he begins his picaresque adventures on the way to London, including love affairs, duels, and imprisonment. Comic, ribald, and highly entertaining, Tom Jones reminds us just how rowdy the eighteenth century got before the nineteenth came and stopped the fun.

8. Labyrinths by Jorge Luis Borges (1964). Simultaneously philosophical and nightmarish, this collection of short stories, parables, and essays popularized both Latin American magic realism as well as metafiction. Borges, a blind Argentine librarian and polymath, here provides almost mathematically concise miniatures—of a man who remembers literally everything, for instance—that read like episodes of The Twilight Zone as written by a metaphysician.

9. W, or The Memory of Childhood by Georges Perec (1975). Perec was an experimental French author fascinated by literary boundaries—one of his novels, A Void, does not contain the letter E. Here, autobiographical chapters recalling (and trying to recall) childhood memories, when most of his family was murdered in the Holocaust, alternate with those telling the fictional story of an Aryan island called W that becomes totalitarian. Gradually, we see that each section says what the other cannot, as the riveting stories form a meta-meditation on narrative form.

9. W, or The Memory of Childhood by Georges Perec (1975). Perec was an experimental French author fascinated by literary boundaries—one of his novels, A Void, does not contain the letter E. Here, autobiographical chapters recalling (and trying to recall) childhood memories, when most of his family was murdered in the Holocaust, alternate with those telling the fictional story of an Aryan island called W that becomes totalitarian. Gradually, we see that each section says what the other cannot, as the riveting stories form a meta-meditation on narrative form.

10. The Makioka Sisters by Junichiro Tanizaki (1943–48). Serialized during wartime, this epic novel chronicles the decline of the Osaka family and the transformation of traditional Japanese society. As their fortunes wither, elder sisters Tsuruko and Sachiko try to preserve the family name and marry off the talented, sensitive Yukiko. All the while the youngest sister, Taeko, aches for freedom from her sisters’ conservatism. Tanizaki uses detailed descriptions of Japanese traditions, such as the tea ceremony, to underscore their fleetingness in an era of rapid modernization.

10. The Makioka Sisters by Junichiro Tanizaki (1943–48). Serialized during wartime, this epic novel chronicles the decline of the Osaka family and the transformation of traditional Japanese society. As their fortunes wither, elder sisters Tsuruko and Sachiko try to preserve the family name and marry off the talented, sensitive Yukiko. All the while the youngest sister, Taeko, aches for freedom from her sisters’ conservatism. Tanizaki uses detailed descriptions of Japanese traditions, such as the tea ceremony, to underscore their fleetingness in an era of rapid modernization.

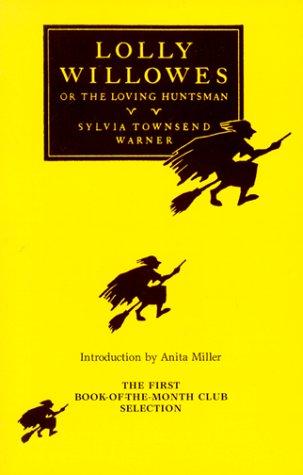

Wild Card: Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1926). The first-ever pick of the Book of the Month Club, Warner’s debut novel is a fantastical light comedy with feminist overtones. Lolly is a forty-seven-year-old spinster whose yearnings impel her to leave her London family for life in the rural village of Great Mop. With the help of a black cat, she enters “into a compact with the devil.” It turns out that this sleepy village—and much of Europe—is full of witches who are less menacing than bohemian. They “know they are dynamite,” she says of these women, “and long for the concussion that may justify them.”

Wild Card: Lolly Willowes by Sylvia Townsend Warner (1926). The first-ever pick of the Book of the Month Club, Warner’s debut novel is a fantastical light comedy with feminist overtones. Lolly is a forty-seven-year-old spinster whose yearnings impel her to leave her London family for life in the rural village of Great Mop. With the help of a black cat, she enters “into a compact with the devil.” It turns out that this sleepy village—and much of Europe—is full of witches who are less menacing than bohemian. They “know they are dynamite,” she says of these women, “and long for the concussion that may justify them.”