Author Photo And Bio

1. My Life and Other Stories by Anton Chekhov (1860-1906). The son of a freed Russian serf, Anton Chekhov became a doctor who, between the patients he often treated without charge, invented the modern short story. The form had been overdecorated with trick endings and swags of atmosphere. Chekhov freed it to reflect the earnest urgencies of ordinary lives in crises through prose that blended a deeply compassionate imagination with precise description. “He remains a great teacher-healer-sage,” Allan Gurganus observed of Chekhov’s stories, which “continue to haunt, inspire, and baffle.”

1. My Life and Other Stories by Anton Chekhov (1860-1906). The son of a freed Russian serf, Anton Chekhov became a doctor who, between the patients he often treated without charge, invented the modern short story. The form had been overdecorated with trick endings and swags of atmosphere. Chekhov freed it to reflect the earnest urgencies of ordinary lives in crises through prose that blended a deeply compassionate imagination with precise description. “He remains a great teacher-healer-sage,” Allan Gurganus observed of Chekhov’s stories, which “continue to haunt, inspire, and baffle.”

2. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962). “It is the commentator who has the last word,” claims Charles Kinbote in this novel masquerading as literary criticism. The text of the book includes a 999-line poem by the murdered American poet John Shade and a line-by-line commentary by Kinbote, a scholar from the country of Zembla. Nabokov even provides an index to this playful, provocative story of poetry, interpretation, identity, and madness, which is full to bursting with allusions, tricks, and the author’s inimitable wordplay.

2. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962). “It is the commentator who has the last word,” claims Charles Kinbote in this novel masquerading as literary criticism. The text of the book includes a 999-line poem by the murdered American poet John Shade and a line-by-line commentary by Kinbote, a scholar from the country of Zembla. Nabokov even provides an index to this playful, provocative story of poetry, interpretation, identity, and madness, which is full to bursting with allusions, tricks, and the author’s inimitable wordplay.

3. A Far Cry from Kensington by Muriel Spark (1988). Like all of Spark’s work, this novel is hard to define. Metaphysical farce? Literary mystery? At bottom, it is a dark, elegant, hilarious tale centered on the zaftig widow Mrs. Hawkins. She spends her days and evenings giving advice to her eccentric rooming housemates and her coworkers in book publishing. Blackmail, suicide, and a crash diet power this story, but it is Spark’s all-too evident disgust with the business end of literature that gives the story its special kick.

3. A Far Cry from Kensington by Muriel Spark (1988). Like all of Spark’s work, this novel is hard to define. Metaphysical farce? Literary mystery? At bottom, it is a dark, elegant, hilarious tale centered on the zaftig widow Mrs. Hawkins. She spends her days and evenings giving advice to her eccentric rooming housemates and her coworkers in book publishing. Blackmail, suicide, and a crash diet power this story, but it is Spark’s all-too evident disgust with the business end of literature that gives the story its special kick.

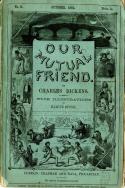

4. Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (1864–65). A miserly father dies and leaves his fortune to his estranged son —so long as he marries a woman he’s never met. While returning home, John Harmon appears to be murdered. He survives and goes undercover. As John Rokesmith, he becomes secretary to the man next in line for his father’s estate, Mr. Boffin. Clever coincidences and revelations follow in this novel notable for its wickedly funny treatment of middle-class society.

4. Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens (1864–65). A miserly father dies and leaves his fortune to his estranged son —so long as he marries a woman he’s never met. While returning home, John Harmon appears to be murdered. He survives and goes undercover. As John Rokesmith, he becomes secretary to the man next in line for his father’s estate, Mr. Boffin. Clever coincidences and revelations follow in this novel notable for its wickedly funny treatment of middle-class society.

5. Collected Poems of Elizabeth Bishop (1911-79). Bishop's poems combine humor and sadness, pain and acceptance, and observe nature and lives in perfect miniaturist close-up. The themes central to her poetry are geography and landscape―from New England, where she grew up, to Brazil and Florida, where she later lived―human connection with the natural world, questions of knowledge and perception, and the ability or inability of form to control chaos. She was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1956 (Poems: North & South – A Cold Spring) and the National Book Award in 1970 for her body of work to that point.

5. Collected Poems of Elizabeth Bishop (1911-79). Bishop's poems combine humor and sadness, pain and acceptance, and observe nature and lives in perfect miniaturist close-up. The themes central to her poetry are geography and landscape―from New England, where she grew up, to Brazil and Florida, where she later lived―human connection with the natural world, questions of knowledge and perception, and the ability or inability of form to control chaos. She was awarded a Pulitzer Prize in 1956 (Poems: North & South – A Cold Spring) and the National Book Award in 1970 for her body of work to that point.

6. Scoop by Evelyn Waugh (1938). This gloriously savage satire of the predatory, pack-like nature of London journalism drew on Waugh’s experience covering Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia for the Daily Mail during the 1930s. It chronicles the unlikely journalistic success of William Boot, a young man of genteel poverty who is mistakenly hired as a foreign correspondent for a London paper, the Daily Beast. Dispatched to the fictional African nation of Ishmaelia, where “a very promising little war” has commenced, Boot manages to scoop the competition despite his good-natured incompetence.

6. Scoop by Evelyn Waugh (1938). This gloriously savage satire of the predatory, pack-like nature of London journalism drew on Waugh’s experience covering Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia for the Daily Mail during the 1930s. It chronicles the unlikely journalistic success of William Boot, a young man of genteel poverty who is mistakenly hired as a foreign correspondent for a London paper, the Daily Beast. Dispatched to the fictional African nation of Ishmaelia, where “a very promising little war” has commenced, Boot manages to scoop the competition despite his good-natured incompetence.

7. Couples by John Updike (1968). One of the signature novels of the American 1960s, this novel scandalized the public with prose pictures of the way people pushed the limits of their newfound freedom in the “post-Pill paradise” by chronicling the interactions of ten young married couples in a seaside New England community who make a cult of sex and of themselves. This group of acquaintances forms a magical circle, complete with ritualistic games, religious substitutions, a priest (Freddy Thorne), and a scapegoat (Piet Hanema). As with most American utopias, this one’s existence is brief and unsustainable, but the “imaginative quest” that inspires its creation is eternal.

7. Couples by John Updike (1968). One of the signature novels of the American 1960s, this novel scandalized the public with prose pictures of the way people pushed the limits of their newfound freedom in the “post-Pill paradise” by chronicling the interactions of ten young married couples in a seaside New England community who make a cult of sex and of themselves. This group of acquaintances forms a magical circle, complete with ritualistic games, religious substitutions, a priest (Freddy Thorne), and a scapegoat (Piet Hanema). As with most American utopias, this one’s existence is brief and unsustainable, but the “imaginative quest” that inspires its creation is eternal.

8. The Life of Henri Brulard by Stendhal (1890). (See William's appreciation below.)

8. The Life of Henri Brulard by Stendhal (1890). (See William's appreciation below.)

9. The Bottle Factory Outing by Beryl Bainbridge (1974). Inspired by the author’s experiences working as a cellar girl, this dark comedy follows two unlikely friends in 1970s London. Brenda and Freda share a rundown room in London and toil away at an Italian factory pasting labels onto wine bottles. Brenda, a shy and passive thirty-three-year-old brunette, recently ran away to the city to escape an abusive husband. Freda, meanwhile, is a rebellious twenty-six-year-old blonde with big dreams and a penchant for bossing people around. The two women are the only English workers at the bottling facility, and their presence stirs up trouble – as Freda tries to attract the attention of one manager while Brenda tries to fend off the advances of another. When Freda organizes a company outing, what’s supposed to be a day of freedom and fun turns into a dark and chaotic tragedy in a novel which that explores loneliness and friendship, sexual frustration and personal power, passion and murder.

9. The Bottle Factory Outing by Beryl Bainbridge (1974). Inspired by the author’s experiences working as a cellar girl, this dark comedy follows two unlikely friends in 1970s London. Brenda and Freda share a rundown room in London and toil away at an Italian factory pasting labels onto wine bottles. Brenda, a shy and passive thirty-three-year-old brunette, recently ran away to the city to escape an abusive husband. Freda, meanwhile, is a rebellious twenty-six-year-old blonde with big dreams and a penchant for bossing people around. The two women are the only English workers at the bottling facility, and their presence stirs up trouble – as Freda tries to attract the attention of one manager while Brenda tries to fend off the advances of another. When Freda organizes a company outing, what’s supposed to be a day of freedom and fun turns into a dark and chaotic tragedy in a novel which that explores loneliness and friendship, sexual frustration and personal power, passion and murder.

10. The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene (1948). The story of a good man enmeshed in love, intrigue, and evil in a West African coastal town. Scobie is bound by strict integrity to his role as assistant police commissioner and by severe responsibility to his wife, Louise, for whom he cares with a fatal pity. When Scobie falls in love with the young widow Helen, he finds vital passion again yielding to pity, integrity giving way to deceit and dishonor—a vortex leading directly to murder. As Scobie's world crumbles, his personal crisis makes for a novel that is suspenseful, fascinating, and, finally, tragic.

10. The Heart of the Matter by Graham Greene (1948). The story of a good man enmeshed in love, intrigue, and evil in a West African coastal town. Scobie is bound by strict integrity to his role as assistant police commissioner and by severe responsibility to his wife, Louise, for whom he cares with a fatal pity. When Scobie falls in love with the young widow Helen, he finds vital passion again yielding to pity, integrity giving way to deceit and dishonor—a vortex leading directly to murder. As Scobie's world crumbles, his personal crisis makes for a novel that is suspenseful, fascinating, and, finally, tragic.

Appreciation of Stendhal’s The Life of Henri Brulard by William Boyd

“Stendhal” is a pseudonym. The author’s real name was Marie-Henri Beyle. Stendhal is best known for the great and classic 19th century French novels The Red and the Black (1830) and The Charterhouse of Parma (1839). He was born in Grenoble in 1793 and died in Paris in 1842.

I have chosen his strange autobiography instead of one of his novels because I think it is an extraordinary 19th-century text, one that was only published in 1890, long after Stendhal’s death. It’s not clear why Stendhal chose the title, however. Very quickly he reveals that he himself is “Henri Brulard”—another false identity—and in a way this fact illustrates the astonishing modernity of this memoir. It is both playful, in a literary sense, and very frank.

Stendhal hated his father (and doesn’t spare him) and he hated his native city, Grenoble—“The capital of boredom.” Moreover, the book’s narrative is the opposite of chronological. Ostensibly an account of the author’s early years, it in fact skips forward and back through Stendhal’s life as he pleases, almost as if it were a record of his meandering thoughts. It is also illustrated with copious little hand-drawn sketches, done by Stendhal himself—plans of houses or city streets, schematic landscapes and so forth, that flesh out the story of his life.

The whole concept of the book is wonderfully out-of-left-field. Stendhal’s honesty is very compelling and his spirit seems very contemporary—all his grumbles and irritations, his love affairs—requited and unrequited—his professional ups and downs are candidly and mercilessly recounted. You could imagine Stendhal living today—the tone of voice is so surprisingly contemporary—as there is nothing remotely dated about this autobiography thinly disguised as a biography. Even if you knew nothing about Stendhal or his famous novels you would be held and beguiled, I believe. A unique piece of 19th century life-writing, as we would now describe it.