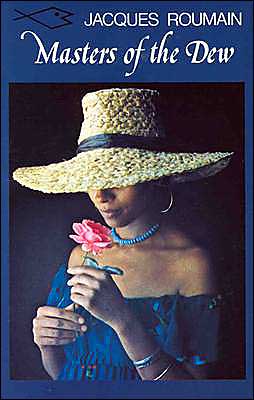

Masters of the Dew by Jacques Roumain (1947).

Masters of the Dew by Jacques Roumain (1947).

Appreciation of Jacques Roumain’s Masters of the Dew by Edwidge Danticat

This novel charmed Langston Hughes and Mercer Cook so much that when they visited Haiti in the 1940s they decided to translate it. Theirs remains the only English translation. This is the plot: A Haitian young man goes to Cuba to cut sugarcane in the 1930s. When he returns to his village in rural Haiti, he finds that a drought has ravaged the entire area and a Romeo and Juliet–type feud between the two most powerful families stands in the community’s way of finding a solution.

Like Romeo, the young man, Manuel, falls in love with the stunning daughter of the family that despises his and a battle ensues that results in tragedy, with some measure of hope. (To say much more would be giving away too much of the plot of this slim volume.) The book has often been called a peasant novel, but it is also an environmental novel, as well as a love story.

I read this book when I was ten years old; it was the first novel in which I recognized people I knew living in circumstances similar to my life and my world. It was also the first time that I realized books could not only help us escape but hold a mirror to our lives, to help us examine a problem and ponder—along with the characters—a possible solution. It was my first engagée or socially engaged novel, one that showed me that the novel could have many roles, that fiction could be used for different purposes without losing its artistic merit. It made me want to write the types of books that could inform and entertain as well as help others live, through a powerful narrative, a heartbreaking, painful, and even redemptive experience.

Total Points: 1 (ED 1)

Harold and the Purple Crayon by Crockett Johnson (1955). “One night Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight.” But there was no moon. So the little boy drew one with his purple crayon. Then he drew a path to walk on. Soon he was using his purple crayon to create real adventures in the forest, ocean, and the air, before drawing a bead for home and bed. Creative, resourceful, and full of surprising purpose, Harold and his trusty crayon reveal the imagination’s power to remake the world.

Harold and the Purple Crayon by Crockett Johnson (1955). “One night Harold decided to go for a walk in the moonlight.” But there was no moon. So the little boy drew one with his purple crayon. Then he drew a path to walk on. Soon he was using his purple crayon to create real adventures in the forest, ocean, and the air, before drawing a bead for home and bed. Creative, resourceful, and full of surprising purpose, Harold and his trusty crayon reveal the imagination’s power to remake the world.

Summer Lightning

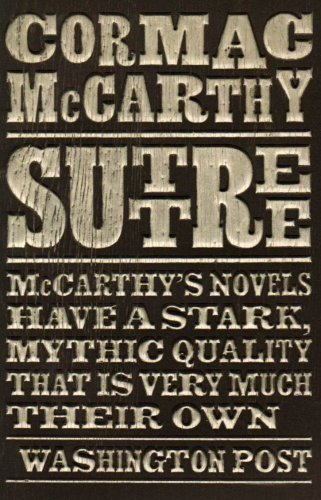

Summer Lightning Suttree

Suttree