The Studs Lonigan trilogy—Young Lonigan (1932), The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan (1934), and Judgment Day (1935)—by James T. Farrell.

The Studs Lonigan trilogy—Young Lonigan (1932), The Young Manhood of Studs Lonigan (1934), and Judgment Day (1935)—by James T. Farrell.

Appreciation of James T. Farrell’s Studs Lonigan Trilogy by Tom Wolfe

To writers born after 1950, James T. Farrell (1904–79) is known, if at all, as a “plodding realist” who wrote a lot of dull, factual novels now as dead and buried as he is. To writers born from, say, 1925 to 1935, however, the very name James T. Farrell strums the heartstrings of youth. To be young and to read Farrell’s first novel, Studs Lonigan! It made one tingle with exhiliration and wonder. How could anybody else understand your own inexpressible feelings so well?

A trio of novels published between 1932 and 1935, the Studs Lonigan trilogy is an account—“story” implies more plot than it actually has—of growing up in a lower-middle-class Irish-Catholic neighborhood in Chicago as Farrell did. He had the wit to make Studs a boy not like himself at all but like the sort of self-willed tough kid who probably made Farrell’s own school days miserable by calling him “Goof” and pulling the goof’s cap down over his eyes, eyeglasses and all. The book’s opening lines stamp Studs’s studied pose indelibly:

Studs Lonigan, on the verge of fifteen, and wearing his first suit of long trousers, stood in the bathroom with a Sweet Caporal pasted in his mug. His hands were jammed in his trouser pockets, and he sneered. He puffed, drew the fag out of his mouth, inhaled and said to himself:

“Well, I’m kissing the old dump goodbye tonight”—the old dump being a parochial junior high school.

I am convinced Farrell wrote those lines as a low-rent reprise to the far more famous lines James Joyce had opened Ulysses with eighteen years earlier: “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed. A yellow dressing gown, ungirdled, was sustained gently behind him by the mild morning air. He held the bowl aloft and intoned:—Introibo ad altare Dei.”

Introibo ad altare Dei. For that bit of showboating by an Irish-Catholic intellectual in Dublin, Farrell had a good low-rent American raspberry: “Well, I’m kissing the old dump”—a Catholic school—”goodbye tonight.”

Farrell, plodding realism and all, was quite conscious of Joyce and all other experimental writing of the early twentieth century. In Studs Lonigan he continually uses Joyce’s most famous device, stream of consciousness, and in a more sophisticated way than the maestro. He just doesn’t feel the need to keep prodding the reader with his elbow as if to say, “Be alert. This is experimental writing.”

It is precisely through Joycean stream of conciousness that Farrell brings us beneath Studs’s hide, which the fourteen-year-old boy keeps as thick as he can, and shows us the tenderness, the love, and the sense of beauty Studs will do anything to prevent the world, meaning the other boys his age on the block, from detecting.

To me, section IV of Chapter Four of the first novel, Young Lonigan, is one of the few sublime reflections of the feeling of being in love in all of literature. One scorching hot Chicago afternoon in early July when “life, along Indiana Avenue, was crawlingly lazy,” Studs goes for a walk in Washington Park with the prettiest girl on the block, Lucy Scanlan. As the two fourteen-year-olds head for the park’s wooded island, “Studs felt, knew, that it was going to be a great afternoon, different from every other afternoon in his whole life.”

They cross the log bridge over onto the island and decide to climb up beneath the leafy dome of a huge oak tree and sit on a branch. Up in the tree it is as if they are removed from . . . the world . . . where Studs feels obliged to be so tough:

The breeze playing upon them through the tree leaves was fine. Studs just sat there and let it play upon him, let it sift through his hair. . . . The wind seemed to Studs like the fingers of a girl, of Lucy, and when it moved through the leaves it was like a girl, like Lucy, running her hand over very expensive silk, like the silk movie actresses wore in the pictures. . . . They sat. Studs swinging his legs, and Lucy swinging hers, she chattering, himself not listening to it, only knowing that it was nice, and that she laughed and talked and was like an angel, and she was an angel playing in the sun. Suddenly, he thought of feeling her up, and he told himself he was a bastard for having such thoughts. He wasn’t worthy of her, even of her fingernail, and he side-glanced at her, and he loved her, he loved her with his hands, and his lips, and his eyes, and his heart, and he loved everything about her, her dress, and voice, and the way she smiled, and her eyes, and her hair, and Lucy, all of her.

With that, Studs has enclosed himself in the cocoon of perfect love, sublime love. A century of psychologists and neuroscientists perfect in their rationalism—not to mention Studs’s gottabe tough, therefore gottabe carnal, therefore gottabe perfectly cynical adolescent cohorts, such as the wonderfully named fourteen-year-old Weary Reilly—have taught us that such “sublime” moments are merely subliminal wafts on the way to the one goal, which is no loftier than that of dogs in the park, namely, the old in and out.

But Studs consciously, or stream-of-consciously, rejects such . . . rationalism . . . dismisses the notion of “feeling her up” and reduces the world to two people or perhaps only one. “They sat.” Farrell keeps repeating that sentence until it is like the ticking of a very big old clock. Studs and Lucy sat high up on a tree limb within a bower of leaves so thick, they shut out everything except the glittering surface of the lagoon and the sounds of children. There was no outside world. There was only Lucy, every perfect breath she breathed, every perfect morsel of her existence. Who, including any of the 20,000 attendees at the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience, can truthfully say that sublime feeling of two creatures dissolving into a single soul is not more thrilling than, in Rabelais’s phrase, playing the two-backed beast?

“He wanted the afternoon never to end, so that he and Lucy could sit there forever; her hands stole timidly into his, and he forgot everything in the world but Lucy. . . . And Time passed through their afternoon like a gentle, tender wind, and like death that was silent and cruel. . . . They sat, and about them their beautiful afternoon evaporated, split up and died like sun that was dying a red death in the calm sky.”

This invocation of death—red, silent, and cruel—creates a mood of foreboding, if my own reaction to it is any measure. The next thing Studs knows, there are graffiti scrawled on walls along Indiana Avenue reading studs loves lucy . . . lucy is crazy about studs . . . and others in that vein. Studs feels like a goof—the term boys used seventy years ago to mean dork—and hastily puts back on his bullet-proof vestments of gottabe tough, therefore gottabe carnal, therefore gottabe cynical. They had sat . . . and that afternoon up in the tree, we eventually learn, was to be the last touch of the sublime in Studs Lonigan’s short life.

The Studs Lonigan trilogy eventually totalled 919 pages. The life of every individual, sayeth the sage, runs along the line created by the intersection of two planes: personality and social setting. I can’t think of any American novelist who ever drew that line more brilliantly than James T. Farrell in this trilogy. If this be “plodding realism,” let every American novelist start plodding Studs-style, lest the American novel fall down in a heap and die, as it now seems wont to do.

Total Points: 3 (TW 3)

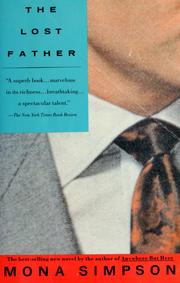

The Lost Father by Mona Simpson (1992). Featuring the heroine from Anywhere but Here, the novel tracks Mayan Atassi’s search across two continents and to the point of madness for the man who has become her God—the father who abandoned her.

The Lost Father by Mona Simpson (1992). Featuring the heroine from Anywhere but Here, the novel tracks Mayan Atassi’s search across two continents and to the point of madness for the man who has become her God—the father who abandoned her. The Lottery and Other Stories

The Lottery and Other Stories

The Quiet American

The Quiet American

(2)

(2)