Author Photo And Bio

Picks in chronological order with Coover's comments.

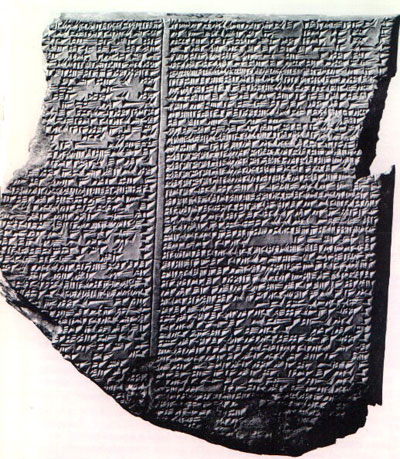

1. The Epic of Gilgamesh (18th century B.C.E.?). The ur-narrative and a kind of secret text for initiates (i.e., other writers).

1. The Epic of Gilgamesh (18th century B.C.E.?). The ur-narrative and a kind of secret text for initiates (i.e., other writers).

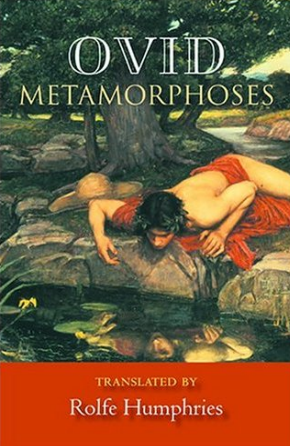

2. Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 c.e.). The poet. Unmatched in all of literary history.

2. Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 c.e.). The poet. Unmatched in all of literary history.

3. The Celestina (1499), probably by Fernando de Rojas. Both ur-novel and ur-drama at the same time. Second greatest work in the Spanish language.

3. The Celestina (1499), probably by Fernando de Rojas. Both ur-novel and ur-drama at the same time. Second greatest work in the Spanish language.

4. Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quijote (1605, 1615). The hidalgo who sallied forth and launched a form that would dominate for over four centuries. Greatest work in the Spanish language and one of the greatest in any language.

4. Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quijote (1605, 1615). The hidalgo who sallied forth and launched a form that would dominate for over four centuries. Greatest work in the Spanish language and one of the greatest in any language.

5. The Collected Shakespeare, contemporary of Cervantes and greatest writer in his own language. It would be hard to choose a single work. Those that I have been closest to all my life are The Tempest (1610), King Lear (1605) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595), though my favorites of the moment change from season to season, performance to performance.

5. The Collected Shakespeare, contemporary of Cervantes and greatest writer in his own language. It would be hard to choose a single work. Those that I have been closest to all my life are The Tempest (1610), King Lear (1605) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1595), though my favorites of the moment change from season to season, performance to performance.

6. Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), my choice as the greatest American novel. The beast we’re all chasing. Melville my inspiration and guide in difficult times.

6. Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), my choice as the greatest American novel. The beast we’re all chasing. Melville my inspiration and guide in difficult times.

7. James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). None can match it for depth, breadth, artistry. As Shakespeare’s plays rise and fall in my affections from year to year, so too do the chapters and voices of Ulysses. At the moment, it’s the Ithaca chapter, which didn’t touch me at all the first time through.

7. James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922). None can match it for depth, breadth, artistry. As Shakespeare’s plays rise and fall in my affections from year to year, so too do the chapters and voices of Ulysses. At the moment, it’s the Ithaca chapter, which didn’t touch me at all the first time through.

8. Jorge Luis Borges’ Ficciones (1944) his breakthrough book, though it’s difficult to limit Borges to particular texts, and it’s probably better to choose Labyrinths, as that book anthologizes Ficciones and several other books. All his writings, including his essays and poetry, are of a piece and hugely influential throughout the world.

8. Jorge Luis Borges’ Ficciones (1944) his breakthrough book, though it’s difficult to limit Borges to particular texts, and it’s probably better to choose Labyrinths, as that book anthologizes Ficciones and several other books. All his writings, including his essays and poetry, are of a piece and hugely influential throughout the world.

9. Samuel Beckett: really his entire opus from Whoroscope to Stirrings Still. If I had to make a choice, I’d probably fudge a bit and take his novel trilogy, simply because it’s bigger than anything else, even though I prefer his short prose and his plays, long and short. The writer who, life long, has meant the most to me and served, distantly, as mentor.

9. Samuel Beckett: really his entire opus from Whoroscope to Stirrings Still. If I had to make a choice, I’d probably fudge a bit and take his novel trilogy, simply because it’s bigger than anything else, even though I prefer his short prose and his plays, long and short. The writer who, life long, has meant the most to me and served, distantly, as mentor.

10. Through the first nine, there’s always room for one more. Now suddenly that door closes. Outside, clamoring not to be excluded are the likes of Homer, Aeschylus and Euripides, Dante, Boccaccio, Chaucer, Rabelais, the Gawain poet and Thomas Malory, Goldoni and Molière, Goethe, Jonathan Swift, Dickens and Dostoevsky, Twain, Baudelaire and Dickinson, Proust, Mann, Kafka, the list goes on and it’s mostly a list only of narrative writers of the Western world, and does not even extend to my generation. Within which, my own writing life has been bound up somewhat with the recent generation of Latin American writers like Donoso, Cortázar, Onetti (to speak only of those no longer among the living), though if I were to single out a particular work, it might be Miguel Ángel Asturias’ El Señor Presidente, or else José Donoso’s Obscene Bird of Night. Rather than make a choice, though, not to dishearten the others, I’ll leave them all outside the door, each knowing there might still be room inside.