Author Photo And Bio

1. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869). Mark Twain supposedly said of this masterpiece, “Tolstoy carelessly neglects to include a boat race.” Everything else is included in this epic novel that revolves around Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Tolstoy is as adept at drawing panoramic battle scenes as he is at describing individual feeling in hundreds of characters from all strata of society, but it is his depiction of Prince Andrey, Natasha, and Pierre —who struggle with love and with finding the right way to live —that makes this book beloved.

1. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869). Mark Twain supposedly said of this masterpiece, “Tolstoy carelessly neglects to include a boat race.” Everything else is included in this epic novel that revolves around Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Tolstoy is as adept at drawing panoramic battle scenes as he is at describing individual feeling in hundreds of characters from all strata of society, but it is his depiction of Prince Andrey, Natasha, and Pierre —who struggle with love and with finding the right way to live —that makes this book beloved.

2. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

2. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

3. Tender Is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1934). The heartbreaking, semiautobiographical story of two expatriate Americans living in France during the 1920s: a gifted young psychiatrist, Dick Diver, and the wealthy, troubled patient who becomes his wife. In this tragic tale of romance and character, her lush lifestyle soon begins to destroy Diver, as alcohol, infidelities, and mental illness claim his hopes. Of the book, Fitzgerald wrote, “Gatsby was a tour de force, but this is a confession of faith.”

3. Tender Is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1934). The heartbreaking, semiautobiographical story of two expatriate Americans living in France during the 1920s: a gifted young psychiatrist, Dick Diver, and the wealthy, troubled patient who becomes his wife. In this tragic tale of romance and character, her lush lifestyle soon begins to destroy Diver, as alcohol, infidelities, and mental illness claim his hopes. Of the book, Fitzgerald wrote, “Gatsby was a tour de force, but this is a confession of faith.”

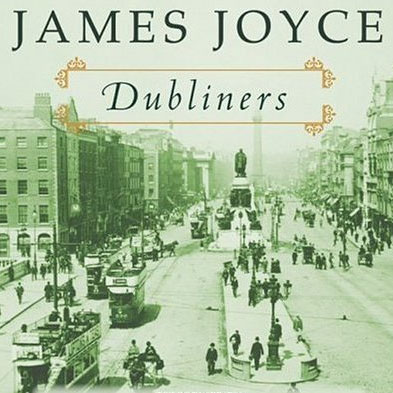

4. Dubliners by James Joyce (1916). Although many of these largely autobiographical stories evoke themes of death, illness, and stasis, nearly all offer their characters redemption —or at least momentary self-knowledge —through what Joyce called “epiphanies,” in which defeat or disappointment is transformed by a sudden, usually life-altering flash of awareness. The collection’s emotional centerpiece is its concluding tale, “The Dead,” which moves from a New Year’s Eve party where guests muse about issues of the day —the Catholic church, Irish nationalism, Freddie Malins’s worrying drunkenness —to a man’s discovery of his wife weeping over a boy who died for love of her. A profound portrait of identity and loneliness, it is Joyce’s most compassionate work.

4. Dubliners by James Joyce (1916). Although many of these largely autobiographical stories evoke themes of death, illness, and stasis, nearly all offer their characters redemption —or at least momentary self-knowledge —through what Joyce called “epiphanies,” in which defeat or disappointment is transformed by a sudden, usually life-altering flash of awareness. The collection’s emotional centerpiece is its concluding tale, “The Dead,” which moves from a New Year’s Eve party where guests muse about issues of the day —the Catholic church, Irish nationalism, Freddie Malins’s worrying drunkenness —to a man’s discovery of his wife weeping over a boy who died for love of her. A profound portrait of identity and loneliness, it is Joyce’s most compassionate work.

5. Stories of Isaac Babel (1894–1940). “Let me finish my work” was Babel’s final plea before he was executed for treason on the orders of Josef Stalin. Though incomplete, his work is enduring. In addition to plays and screenplays, some in collaboration with Sergei Eisenstein, Babel made his mark with The Odessa Stories, which focused on gangsters from his native city, and even more important, the collection entitled Red Cavalry. Chaos, bloodshed, and mordant fatalism dominate those interconnected stories, set amid the Red Army’s Polish campaign during the Russian Civil War. Babel, himself a combat veteran, embodied the war’s extremes in the (doubtless autobiographically based) war correspondent–propagandist Kiril Lyutov and the brutally violent Cossack soldiers whom he both fears and admires. Several masterpieces herein (including “A Letter,” “My First Goose,” and “Berestechko”) anticipate Hemingway’s later achievement, and confirm Babel’s place among the great modernist writers.

5. Stories of Isaac Babel (1894–1940). “Let me finish my work” was Babel’s final plea before he was executed for treason on the orders of Josef Stalin. Though incomplete, his work is enduring. In addition to plays and screenplays, some in collaboration with Sergei Eisenstein, Babel made his mark with The Odessa Stories, which focused on gangsters from his native city, and even more important, the collection entitled Red Cavalry. Chaos, bloodshed, and mordant fatalism dominate those interconnected stories, set amid the Red Army’s Polish campaign during the Russian Civil War. Babel, himself a combat veteran, embodied the war’s extremes in the (doubtless autobiographically based) war correspondent–propagandist Kiril Lyutov and the brutally violent Cossack soldiers whom he both fears and admires. Several masterpieces herein (including “A Letter,” “My First Goose,” and “Berestechko”) anticipate Hemingway’s later achievement, and confirm Babel’s place among the great modernist writers.

6. Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather (1927). Two French missionaries come to the vast and untamed deserts of New Mexico in 1851. Through a series of often symbolic stories about their shared and personal experiences over forty years, Cather depicts both vanished landscapes and timeless themes of faith, loneliness, and our relationships with one another and the natural world.

6. Death Comes for the Archbishop by Willa Cather (1927). Two French missionaries come to the vast and untamed deserts of New Mexico in 1851. Through a series of often symbolic stories about their shared and personal experiences over forty years, Cather depicts both vanished landscapes and timeless themes of faith, loneliness, and our relationships with one another and the natural world.

7. The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy (1886). In the first chapter Michael Henchard sells his wife and child at a country fair. When he meets his forsaken wife Susan and daughter Elizabeth-Jane years later, he is no longer a drunken hay-trusser but mayor of his town. Henchard has improved his position in life but not his disposition, and this tragedy of misplaced pride, torturous guilt, and immense bitterness is vintage Hardy.

7. The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy (1886). In the first chapter Michael Henchard sells his wife and child at a country fair. When he meets his forsaken wife Susan and daughter Elizabeth-Jane years later, he is no longer a drunken hay-trusser but mayor of his town. Henchard has improved his position in life but not his disposition, and this tragedy of misplaced pride, torturous guilt, and immense bitterness is vintage Hardy.

8. Daniel Deronda by George Eliot (1874–76). Daniel Deronda first sees Gwendolyn Harleth gambling at a fashionable resort and asks himself whether “the good or evil genius is dominant” in her. He is a man of ideas; she is an egotistical, spoiled girl. Can Daniel redeem her? Another character who needs saving is Mirah Cohen, yet through her, Daniel finds a form of salvation by discovering his hidden Jewish heritage in this novel that exposes the deeply rooted anti-Semitism of Victorian England.

8. Daniel Deronda by George Eliot (1874–76). Daniel Deronda first sees Gwendolyn Harleth gambling at a fashionable resort and asks himself whether “the good or evil genius is dominant” in her. He is a man of ideas; she is an egotistical, spoiled girl. Can Daniel redeem her? Another character who needs saving is Mirah Cohen, yet through her, Daniel finds a form of salvation by discovering his hidden Jewish heritage in this novel that exposes the deeply rooted anti-Semitism of Victorian England.

9. The Marquise of O — and Other Stories by Heinrich von Kleist (1777–1811). (See below.)

9. The Marquise of O — and Other Stories by Heinrich von Kleist (1777–1811). (See below.)

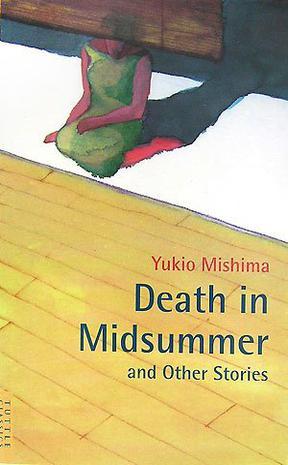

10. Death in Midsummer and Other Stories by Yukio Mishima (1968). The diversity of this collection’s subject and form will surprise anyone who knows only Mishima’s legend, which he carefully created through an ascetic life and a failed attempt to ignite a bushido (samurai) movement in Japan —a move that ended with his ritual suicide in 1970. The tales —including a Noh play, a Buddhist fable, a comedy of manners, and a love triangle among three men —all reflect Mishima’s profound alienation from the drift and purposelessness of modern life.

10. Death in Midsummer and Other Stories by Yukio Mishima (1968). The diversity of this collection’s subject and form will surprise anyone who knows only Mishima’s legend, which he carefully created through an ascetic life and a failed attempt to ignite a bushido (samurai) movement in Japan —a move that ended with his ritual suicide in 1970. The tales —including a Noh play, a Buddhist fable, a comedy of manners, and a love triangle among three men —all reflect Mishima’s profound alienation from the drift and purposelessness of modern life.

Appreciation of the von Kleist’s The Marquis of O by Paula Fox

Heinrich von Kleist was born in 1777 and killed himself thirty-five years later in a suicide pact with a young lady, after having been blessed, or cursed, with a formidable talent for writing. During his brief life he turned out eight plays, among which is the marvelous one-act Robert Guiscard; eight stories, including the novella Michael Kohlaas; and a long story, The Marquise of O—. He also wrote a philosophical discourse, “On the Puppet Theatre,” a group of anecdotes, and some brilliant journalism.

Von Kleist was a true Romantic, yet he is utterly modern in the swiftness and depth of his perception of his subjects. Perhaps he didn’t choose them —they chose him, as it often seems with such a writer, a kind of fatality of choice.

In Michael Kohlaas von Kleist writes of the passion for justice turning a man into an outlaw. In The Beggarwoman of Locarno, a three-page arrow of a short story, a man sets fire to his own house. The Marquise of O —begins with an advertisement, placed in journals by a widowed Marquise, that pleads for the father of the child she is carrying to come forward and marry her. She hasn’t the faintest idea how her pregnancy came about.

And here’s the remarkable opening line of “The Earthquake in Chile”: “In Santiago, the capital of the kingdom of Chile, at the very moment of the great earthquake of 1647 in which many thousands of lives were lost, a young Spaniard by the name of Jeronimo Rugera, who had been locked up on a criminal charge, was standing against a prison pillar, about to hang himself.”

There are other stories of so lyrical yet violent a nature that the reader is infected with a fever of interest and admiration; at least this reader.