Author Photo And Bio

1. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877). Anna’s adulterous love affair with Count Vronsky—which follows an inevitable, devastating road from their dizzyingly erotic first encounter at a ball to Anna’s exile from society and her famous, fearful end—is a masterwork of tragic love. What makes the novel so deeply satisfying, though, is how Tolstoy balances the story of Anna’s passion with a second semiautobiographical story of Levin’s spirituality and domesticity. Levin commits his life to simple human values: his marriage to Kitty, his faith in God, and his farming. Tolstoy enchants us with Anna’s sin, then proceeds to educate us with Levin’s virtue.

1. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1877). Anna’s adulterous love affair with Count Vronsky—which follows an inevitable, devastating road from their dizzyingly erotic first encounter at a ball to Anna’s exile from society and her famous, fearful end—is a masterwork of tragic love. What makes the novel so deeply satisfying, though, is how Tolstoy balances the story of Anna’s passion with a second semiautobiographical story of Levin’s spirituality and domesticity. Levin commits his life to simple human values: his marriage to Kitty, his faith in God, and his farming. Tolstoy enchants us with Anna’s sin, then proceeds to educate us with Levin’s virtue.

2. The Charterhouse of Parma by Stendhal (1839). (See Francine's appreciation below.)

2. The Charterhouse of Parma by Stendhal (1839). (See Francine's appreciation below.)

3. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

3. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

4. Stories of Anton Chekhov (1860–1904). The son of a freed Russian serf, Anton Chekhov became a doctor who, between the patients he often treated without charge, invented the modern short story. The form had been overdecorated with trick endings and swags of atmosphere. Chekhov freed it to reflect the earnest urgencies of ordinary lives in crises through prose that blended a deeply compassionate imagination with precise description. “He remains a great teacher-healer-sage,” Allan Gurganus observed of Chekhov’s stories, which “continue to haunt, inspire, and baffle.”

4. Stories of Anton Chekhov (1860–1904). The son of a freed Russian serf, Anton Chekhov became a doctor who, between the patients he often treated without charge, invented the modern short story. The form had been overdecorated with trick endings and swags of atmosphere. Chekhov freed it to reflect the earnest urgencies of ordinary lives in crises through prose that blended a deeply compassionate imagination with precise description. “He remains a great teacher-healer-sage,” Allan Gurganus observed of Chekhov’s stories, which “continue to haunt, inspire, and baffle.”

5. Stories of John Cheever (1912–82). Seemingly confined to recording the self-inflations and petty hypocrisies of suburban WASPs, Cheever’s short fiction actually redefined the story form, mixing minimalism and myth to create uniquely American tragicomedy. A master of the ambiguous ending, Cheever could also be direct: In “The Swimmer,” a man dreams of his family as he blithely “swims” home through his neighbors’ backyard pools, only to collapse at the door of his empty, locked house.

5. Stories of John Cheever (1912–82). Seemingly confined to recording the self-inflations and petty hypocrisies of suburban WASPs, Cheever’s short fiction actually redefined the story form, mixing minimalism and myth to create uniquely American tragicomedy. A master of the ambiguous ending, Cheever could also be direct: In “The Swimmer,” a man dreams of his family as he blithely “swims” home through his neighbors’ backyard pools, only to collapse at the door of his empty, locked house.

6. Stories of Mavis Gallant (1922– ). Expatriate experience and cultural contrasts energize the knowing, roomy fiction of the native Canadian, sometime Parisian, master. Praised for her story sequences (such as the semiautobiographical Linnet Muir tales and those focused on aging French author Henri Grippes), Gallant also excels in generously detailed depictions of an unwanted arranged marriage (“Across the Bridge”), a German POW’s survival skills (“Ernst in Civilian Clothes”), and numerous other vivid dramatizations of displacement and rootlessness (such as “The Ice Wagon Going Down the Street,” “The Four Seasons”).

6. Stories of Mavis Gallant (1922– ). Expatriate experience and cultural contrasts energize the knowing, roomy fiction of the native Canadian, sometime Parisian, master. Praised for her story sequences (such as the semiautobiographical Linnet Muir tales and those focused on aging French author Henri Grippes), Gallant also excels in generously detailed depictions of an unwanted arranged marriage (“Across the Bridge”), a German POW’s survival skills (“Ernst in Civilian Clothes”), and numerous other vivid dramatizations of displacement and rootlessness (such as “The Ice Wagon Going Down the Street,” “The Four Seasons”).

7. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

7. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

8. Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871–72). Dorothea Brooke is a pretty young idealist whose desire to improve the world leads her to marry the crusty pedant Casaubon. This mistake takes her down a circuitous and painful path in search of happiness. The novel, which explores society’s brakes on women and deteriorating rural life, is as much a chronicle of the English town of Middlemarch as it is the portrait of a lady. Eliot excels at parsing moments of moral crisis so that we feel a character’s anguish and resolve. Her intelligent sympathy for even the most unlikable people redirects our own moral compass toward charity rather than enmity.

8. Middlemarch by George Eliot (1871–72). Dorothea Brooke is a pretty young idealist whose desire to improve the world leads her to marry the crusty pedant Casaubon. This mistake takes her down a circuitous and painful path in search of happiness. The novel, which explores society’s brakes on women and deteriorating rural life, is as much a chronicle of the English town of Middlemarch as it is the portrait of a lady. Eliot excels at parsing moments of moral crisis so that we feel a character’s anguish and resolve. Her intelligent sympathy for even the most unlikable people redirects our own moral compass toward charity rather than enmity.

9. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (1967). Widely considered the most popular work in Spanish since Don Quixote, this novel—part fantasy, part social history of Colombia—sparked fiction’s “Latin boom” and the popularization of magic realism. Over a century that seems to move backward and forward simultaneously, the forgotten and offhandedly magical village of Macondo—home to a Faulknerian plethora of incest, floods, massacres, civil wars, dreamers, prudes, and prostitutes—loses its Edenic innocence as it is increasingly exposed to civilization.

9. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (1967). Widely considered the most popular work in Spanish since Don Quixote, this novel—part fantasy, part social history of Colombia—sparked fiction’s “Latin boom” and the popularization of magic realism. Over a century that seems to move backward and forward simultaneously, the forgotten and offhandedly magical village of Macondo—home to a Faulknerian plethora of incest, floods, massacres, civil wars, dreamers, prudes, and prostitutes—loses its Edenic innocence as it is increasingly exposed to civilization.

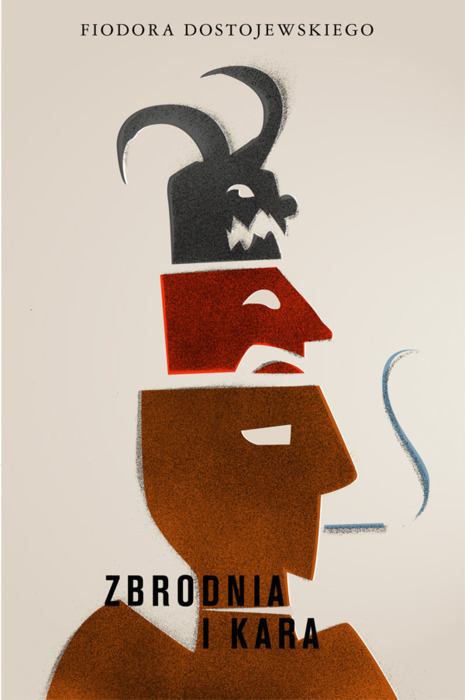

10. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

10. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

Appreciation of Stendhal’s The Charterhouse of Parma by Francine Prose

Opening The Charterhouse of Parma is like stepping into the path of a benevolent cyclone that will pick you up and set you down, gently but firmly, somewhere else. You can still feel the tailwind of inspiration, the high speed at which Stendhal wrote it, and you can’t help admiring its assurance and audacity.

Stendhal marks the boundaries of the more traditional nineteenth-century novel, and then proceeds to explode them. Just as Fabrizio keeps discovering that his life is taking a different direction from what he’d imagined, so the reader keeps thinking that Stendhal has written one kind of book, then finding that it is something else entirely. Stendhal writes as if he can’t see why everything—politics, history, intrigue, the battle of Waterloo, a love story, several love stories—can’t be compressed into a single novel. The result is a huge canvas on which every detail is painted with astonishing realism and psychological verisimilitude.

First you are totally swept up in Fabrizio’s peculiar experience of the Napoleonic wars, then moved by the Krazy Kat love triangle involving Fabrizio, Mosca, and Gina, and throughout, astonished by the accuracy of Stendhal’s observations on love, jealousy, ambition, and of how the perception of biological age influences our behavior.

I love the way Stendhal uses “Italian” to mean passionate, and how he falls in love with his characters, for all the right reasons. One can only imagine how Tolstoy would have punished Gina, who is not only among the most memorable women in literature, but who is also scheming, casually adulterous, and madly in love with her own nephew. Each time I finish the book, I feel as if the world has been washed clean and polished while I was reading, and as if everything around me is shining a little more brightly.