Author Photo And Bio

1. Hamlet by William Shakespeare (1600). The most famous play ever written, Hamlet tells the story of a melancholic prince charged with avenging the murder of his father at the hands of his uncle, who then married his mother and, becoming King of Denmark, robbed Hamlet of the throne. Told the circumstances of this murder and usurpation by his father’s ghost, Hamlet is plunged deep into brilliant and profound reflection on the problems of existence, which meditations delay his revenge at the cost of innocent lives. When he finally acts decisively, Hamlet takes with him every remaining major character in a crescendo of violence unmatched in Shakespearean theater.

1. Hamlet by William Shakespeare (1600). The most famous play ever written, Hamlet tells the story of a melancholic prince charged with avenging the murder of his father at the hands of his uncle, who then married his mother and, becoming King of Denmark, robbed Hamlet of the throne. Told the circumstances of this murder and usurpation by his father’s ghost, Hamlet is plunged deep into brilliant and profound reflection on the problems of existence, which meditations delay his revenge at the cost of innocent lives. When he finally acts decisively, Hamlet takes with him every remaining major character in a crescendo of violence unmatched in Shakespearean theater.

2. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605, 1615). Considered literature’s first great novel, Don Quixote is the comic tale of a dream-driven nobleman whose devotion to medieval romances inspires him to go in quest of chivalric glory and the love of a lady who doesn’t know him. Famed for its hilarious antics with windmills and nags, Don Quixote offers timeless meditations on heroism, imagination, and the art of writing itself. Still, the heart of the book is the relationship between the deluded knight and his proverb-spewing squire, Sancho Panza. If their misadventures illuminate human folly, it is a folly redeemed by simple love, which makes Sancho stick by his mad master “no matter how many foolish things he does.”

2. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605, 1615). Considered literature’s first great novel, Don Quixote is the comic tale of a dream-driven nobleman whose devotion to medieval romances inspires him to go in quest of chivalric glory and the love of a lady who doesn’t know him. Famed for its hilarious antics with windmills and nags, Don Quixote offers timeless meditations on heroism, imagination, and the art of writing itself. Still, the heart of the book is the relationship between the deluded knight and his proverb-spewing squire, Sancho Panza. If their misadventures illuminate human folly, it is a folly redeemed by simple love, which makes Sancho stick by his mad master “no matter how many foolish things he does.”

3. The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (1380s?). Not so much a single poem as a gathering of voices ranging from bawdy to pious, this captivating work presents a panoramic view of medieval England. Vivid, direct, and often irresistibly funny, the tales are told by pilgrims making their way to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Beckett. Each night another member of the party —a knight, a scholar, a miller —tells a story, and tale by tale, a portrait emerges of the diversity and delight of human possibility.

3. The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer (1380s?). Not so much a single poem as a gathering of voices ranging from bawdy to pious, this captivating work presents a panoramic view of medieval England. Vivid, direct, and often irresistibly funny, the tales are told by pilgrims making their way to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas Beckett. Each night another member of the party —a knight, a scholar, a miller —tells a story, and tale by tale, a portrait emerges of the diversity and delight of human possibility.

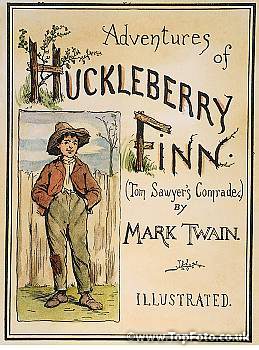

4. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1884). Hemingway proclaimed, “All modern American literature comes from . . . ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ ” But one can read it simply as a straightforward adventure story in which two comrades of conve nience, the parentally abused rascal Huck and fugitive slave Jim, escape the laws and conventions of society on a raft trip down the Mississippi. Alternatively, it’s a subversive satire in which Twain uses the only superficially naïve Huck to comment bitingly on the evils of racial bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and capitalist greed he observes in a host of other largely unsympathetic characters. Huck’s climactic decision to “light out for the Territory ahead of the rest” rather than submit to the starched standards of “civilization” reflects a uniquely American strain of individualism and nonconformity stretching from Daniel Boone to Easy Rider.

4. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1884). Hemingway proclaimed, “All modern American literature comes from . . . ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ ” But one can read it simply as a straightforward adventure story in which two comrades of conve nience, the parentally abused rascal Huck and fugitive slave Jim, escape the laws and conventions of society on a raft trip down the Mississippi. Alternatively, it’s a subversive satire in which Twain uses the only superficially naïve Huck to comment bitingly on the evils of racial bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and capitalist greed he observes in a host of other largely unsympathetic characters. Huck’s climactic decision to “light out for the Territory ahead of the rest” rather than submit to the starched standards of “civilization” reflects a uniquely American strain of individualism and nonconformity stretching from Daniel Boone to Easy Rider.

5. Light in August by William Faulkner (1932). This novel contains two of Faulkner’s most telling characters, the doggedly optimistic Lena Grove, who is searching for the father of her unborn child, and the doomed Joe Christmas, an orphan of uncertain race and towering rage. Faulkner’s signature concerns about birth and heritage, race, religion, and the inescapable burdens of the past power this fierce, unflinching, yet hopeful novel.

6. The stories of Flannery O’Connor (1925–64). Full of violence, mordant comedy, and a fierce Catholic vision that is bent on human salvation at any cost, Flannery O’Connor’s stories are like no others. Bigots, intellectual snobs, shyster preachers, and crazed religious seers —a full cavalcade of what critics came to call “grotesques”—careen through her tales, and O’Connor gleefully displays the moral inadequacy of all of them. Twentieth-century short stories often focus on tiny moments, but O’Connor’s stories, with their unswerving eye for vanity and their profound sense of the sacred, feel immense.

6. The stories of Flannery O’Connor (1925–64). Full of violence, mordant comedy, and a fierce Catholic vision that is bent on human salvation at any cost, Flannery O’Connor’s stories are like no others. Bigots, intellectual snobs, shyster preachers, and crazed religious seers —a full cavalcade of what critics came to call “grotesques”—careen through her tales, and O’Connor gleefully displays the moral inadequacy of all of them. Twentieth-century short stories often focus on tiny moments, but O’Connor’s stories, with their unswerving eye for vanity and their profound sense of the sacred, feel immense.

7. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930). The Bundrens of Yoknapatawpha County have a simple task —to transport their mother’s body by wagon to her birthplace for burial. Faulkner confronts them with challenges of near biblical proportions in this modernist epic that uses fifteen different psychologically complex first-person narrators (including the dead mother) through its fifty-nine chapters. Soaring language contrasts with the gritty sense of doom in this novel that includes the most famous short chapter in literature: “My mother is a fish.”

7. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner (1930). The Bundrens of Yoknapatawpha County have a simple task —to transport their mother’s body by wagon to her birthplace for burial. Faulkner confronts them with challenges of near biblical proportions in this modernist epic that uses fifteen different psychologically complex first-person narrators (including the dead mother) through its fifty-nine chapters. Soaring language contrasts with the gritty sense of doom in this novel that includes the most famous short chapter in literature: “My mother is a fish.”

8. Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller (1949). A broken Everyman, Willy Loman is about to be fired from his job as a traveling shoe salesman. In response he clings to fantasies —that he is “well liked” and that his troubled sons, Hap and Biff, are bound for greatness. A withering assault on the American Dream, the play is an affecting portrait of a man unable to understand the forces that have shaped his life.

8. Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller (1949). A broken Everyman, Willy Loman is about to be fired from his job as a traveling shoe salesman. In response he clings to fantasies —that he is “well liked” and that his troubled sons, Hap and Biff, are bound for greatness. A withering assault on the American Dream, the play is an affecting portrait of a man unable to understand the forces that have shaped his life.

9. The stories of Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961). Love and war, childhood and adolescence, and initiation and experience are recurring themes in these journalistically spare, often autobiographical stories. Some, including “A Very Short Story,” are merely snapshots, barely a page long. Others, such as Snows of Kilimanjaro” are multi-layered stories within a story. Among the best are those featuring Hemingway’s doppelganger Nick Adams, whose youthful innocence in an Edenic Michigan becomes an almost jaded stoicism through combat and failed romance.

9. The stories of Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961). Love and war, childhood and adolescence, and initiation and experience are recurring themes in these journalistically spare, often autobiographical stories. Some, including “A Very Short Story,” are merely snapshots, barely a page long. Others, such as Snows of Kilimanjaro” are multi-layered stories within a story. Among the best are those featuring Hemingway’s doppelganger Nick Adams, whose youthful innocence in an Edenic Michigan becomes an almost jaded stoicism through combat and failed romance.

10, Candide by Voltaire (1759). In this withering satire of eighteenth-century optimism, Candide wanders the world testing his tutor Pangloss’s belief that we live in the “best of all possible worlds.” When Candide loses his true love, gets flogged in the army, injured in an earthquake, and robbed in the New World, he finally muses, “If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others?” In response to life’s mysteries, he concludes, the best we can do is patiently cultivate our own gardens.

10, Candide by Voltaire (1759). In this withering satire of eighteenth-century optimism, Candide wanders the world testing his tutor Pangloss’s belief that we live in the “best of all possible worlds.” When Candide loses his true love, gets flogged in the army, injured in an earthquake, and robbed in the New World, he finally muses, “If this is the best of all possible worlds, what are the others?” In response to life’s mysteries, he concludes, the best we can do is patiently cultivate our own gardens.