Author Photo And Bio

1. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

1. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

2. Ulysses by James Joyce (1922). Filled with convoluted plotting, scrambled syntax, puns, neologisms, and arcane mythological allusions, Ulysses recounts the misadventures of schlubby Dublin advertising salesman Leopold Bloom on a single day, June 16, 1904. As Everyman Bloom and a host of other characters act out, on a banal and quotidian scale, the major episodes of Homer’s Odyssey —including encounters with modern-day sirens and a Cyclops —Joyce’s bawdy mock-epic suggests the improbability, perhaps even the pointlessness, of heroism in the modern age.

2. Ulysses by James Joyce (1922). Filled with convoluted plotting, scrambled syntax, puns, neologisms, and arcane mythological allusions, Ulysses recounts the misadventures of schlubby Dublin advertising salesman Leopold Bloom on a single day, June 16, 1904. As Everyman Bloom and a host of other characters act out, on a banal and quotidian scale, the major episodes of Homer’s Odyssey —including encounters with modern-day sirens and a Cyclops —Joyce’s bawdy mock-epic suggests the improbability, perhaps even the pointlessness, of heroism in the modern age.

3. Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner (1936). Weaving mythic tales of biblical urgency with the experimental techniques of high modernism, Faulkner bridged the past and future. This is the story of Thomas Sutpen, a rough-hewn striver who came to Mississippi in 1833 with a gang of wild slaves from Haiti to build a dynasty. Almost in reach, his dream is undone by plagues of biblical (and Faulknerian) proportions: racism, incest, war, fratricide, pride, and jealousy. Through the use of multiple narrators, Faulkner turns this gripping Yoknapatawpha saga into a profound and dazzling meditation on truth, memory, history, and literature itself.

3. Absalom, Absalom! by William Faulkner (1936). Weaving mythic tales of biblical urgency with the experimental techniques of high modernism, Faulkner bridged the past and future. This is the story of Thomas Sutpen, a rough-hewn striver who came to Mississippi in 1833 with a gang of wild slaves from Haiti to build a dynasty. Almost in reach, his dream is undone by plagues of biblical (and Faulknerian) proportions: racism, incest, war, fratricide, pride, and jealousy. Through the use of multiple narrators, Faulkner turns this gripping Yoknapatawpha saga into a profound and dazzling meditation on truth, memory, history, and literature itself.

4. Stories of Eudora Welty (1909–2001). (See Louis's appreciation below).

4. Stories of Eudora Welty (1909–2001). (See Louis's appreciation below).

5. The Red and the Black by Stendhal (1830). Stendhal inaugurated French realism with his revolutionary colloquial style and the famous pronouncement, “A novel is a mirror carried along a highway.” Julien Sorel, the tragic antihero, rises from peasant roots through high society. In his character, the “red” of soldiering and a bygone age of heroism vies with the “black” world of the priesthood, careerism, and hypocrisy.

5. The Red and the Black by Stendhal (1830). Stendhal inaugurated French realism with his revolutionary colloquial style and the famous pronouncement, “A novel is a mirror carried along a highway.” Julien Sorel, the tragic antihero, rises from peasant roots through high society. In his character, the “red” of soldiering and a bygone age of heroism vies with the “black” world of the priesthood, careerism, and hypocrisy.

6. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605, 1615). Considered literature’s first great novel, Don Quixote is the comic tale of a dream-driven nobleman whose devotion to medieval romances inspires him to go in quest of chivalric glory and the love of a lady who doesn’t know him. Famed for its hilarious antics with windmills and nags, Don Quixote offers timeless meditations on heroism, imagination, and the art of writing itself. Still, the heart of the book is the relationship between the deluded knight and his proverb-spewing squire, Sancho Panza. If their misadventures illuminate human folly, it is a folly redeemed by simple love, which makes Sancho stick by his mad master “no matter how many foolish things he does.”

6. Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (1605, 1615). Considered literature’s first great novel, Don Quixote is the comic tale of a dream-driven nobleman whose devotion to medieval romances inspires him to go in quest of chivalric glory and the love of a lady who doesn’t know him. Famed for its hilarious antics with windmills and nags, Don Quixote offers timeless meditations on heroism, imagination, and the art of writing itself. Still, the heart of the book is the relationship between the deluded knight and his proverb-spewing squire, Sancho Panza. If their misadventures illuminate human folly, it is a folly redeemed by simple love, which makes Sancho stick by his mad master “no matter how many foolish things he does.”

7. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869). Mark Twain supposedly said of this masterpiece, “Tolstoy carelessly neglects to include a boat race.” Everything else is included in this epic novel that revolves around Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Tolstoy is as adept at drawing panoramic battle scenes as he is at describing individual feeling in hundreds of characters from all strata of society, but it is his depiction of Prince Andrey, Natasha, and Pierre —who struggle with love and with finding the right way to live —that makes this book beloved.

7. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (1869). Mark Twain supposedly said of this masterpiece, “Tolstoy carelessly neglects to include a boat race.” Everything else is included in this epic novel that revolves around Napoleon’s invasion of Russia in 1812. Tolstoy is as adept at drawing panoramic battle scenes as he is at describing individual feeling in hundreds of characters from all strata of society, but it is his depiction of Prince Andrey, Natasha, and Pierre —who struggle with love and with finding the right way to live —that makes this book beloved.

8. Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne (1759–67). Sterne promises the “life and opinions” of his protagonist. Yet halfway through the fourth volume of nine, we are still in the first day of the hero’s life thanks to marvelous digressions and what the narrator calls “unforeseen stoppages”—detailing the quirky habits of his eccentric family members and their friends. This broken narrative is unified by Sterne’s comic touch, which shimmers in this thoroughly entertaining novel that harks back to Don Quixote and foreshadows Ulysses.

8. Tristram Shandy by Laurence Sterne (1759–67). Sterne promises the “life and opinions” of his protagonist. Yet halfway through the fourth volume of nine, we are still in the first day of the hero’s life thanks to marvelous digressions and what the narrator calls “unforeseen stoppages”—detailing the quirky habits of his eccentric family members and their friends. This broken narrative is unified by Sterne’s comic touch, which shimmers in this thoroughly entertaining novel that harks back to Don Quixote and foreshadows Ulysses.

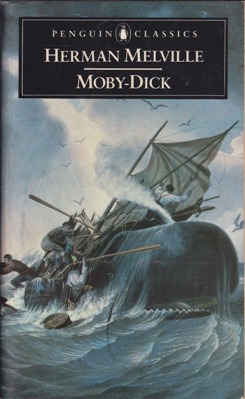

9. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

9. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

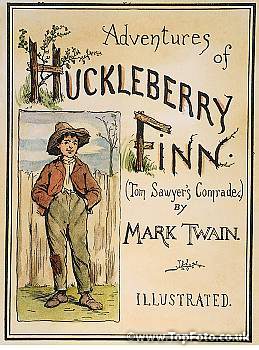

10. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1884). Hemingway proclaimed, “All modern American literature comes from . . . ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ ” But one can read it simply as a straightforward adventure story in which two comrades of conve nience, the parentally abused rascal Huck and fugitive slave Jim, escape the laws and conventions of society on a raft trip down the Mississippi. Alternatively, it’s a subversive satire in which Twain uses the only superficially naïve Huck to comment bitingly on the evils of racial bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and capitalist greed he observes in a host of other largely unsympathetic characters. Huck’s climactic decision to “light out for the Territory ahead of the rest” rather than submit to the starched standards of “civilization” reflects a uniquely American strain of individualism and nonconformity stretching from Daniel Boone to Easy Rider.

10. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1884). Hemingway proclaimed, “All modern American literature comes from . . . ‘Huckleberry Finn.’ ” But one can read it simply as a straightforward adventure story in which two comrades of conve nience, the parentally abused rascal Huck and fugitive slave Jim, escape the laws and conventions of society on a raft trip down the Mississippi. Alternatively, it’s a subversive satire in which Twain uses the only superficially naïve Huck to comment bitingly on the evils of racial bigotry, religious hypocrisy, and capitalist greed he observes in a host of other largely unsympathetic characters. Huck’s climactic decision to “light out for the Territory ahead of the rest” rather than submit to the starched standards of “civilization” reflects a uniquely American strain of individualism and nonconformity stretching from Daniel Boone to Easy Rider.

Appreciation of the Stories of Eudora Welty by Louis D. Rubin Jr.

At first glance, the people Eudora Welty usually writes about seem unremarkable, as are the mostly Mississippi towns, cities, and countryside they live in.

To read her stories, however, such as “Why I Live at the P.O.,” “Petrified Man,” “Powerhouse,” “Moon Lake,” and “Kin,” is to learn otherwise. Through them you enter the realm of the extraordinary, as revealed in the commonplace. Each of Welty’s seemingly mundane people exhibits the depth, complexity, private surmise, and ultimate riddle of human identity. “Every-body to their own visioning,” as one of her characters remarks.

There is plenty of high comedy. Few authors can match her eye for the incongruous, the hilarious response, the bemused quality of the way her people go about their lives. There is also pathos, veering sometimes into tragedy, and beyond that, awareness of what is unknowable and inscrutable.

Her most stunning fiction is the group of interconnected stories published in 1949 as The Golden Apples. These center on the citizenry of Morgana, Mississippi, over the course of some four decades. In “June Recital” German-born Miss Lottie Elisabeth Eckhart teaches piano to the young. These include Cassie Morrison, who carries on her teacher’s mission, and Virgie Rainey, most talented of all, who in spite of herself absorbs “the Beethoven, as with the dragon’s blood.” In the closing story, “The Wanderers,” Virgie sits under a tree not far from Miss Eckhart’s grave and gazes into the falling rain, hearing “the magical percussion” drumming into her ears: “That was the gift she had touched with her fingers that had drifted and left her.”

Welty’s richly allusive style, alive to nuance, is not really like anyone else’s. The dialogue (her characters talk at rather than to one another), the shading of Greek mythology and W. B. Yeats’s poetry into the rhythms of everyday life in Morgana, the depth perception of a major literary artist, all make her stories superb.