Author Photo And Bio

1. The Blazing World by Siri Hustvedt (2014). This provocative novel about perception, prejudice, desire, and one woman’s struggle to be seen tells the story of artist Harriet Burden, who, after years of having her work ignored, ignites an explosive scandal in New York’s art world when she recruits three young men to present her creations as their own. Yet when the shows succeed and Burden steps forward for her triumphant reveal, she is betrayed by the third man, Rune. Many critics side with him, and Burden and Rune find themselves in a charged and dangerous game, one that ends in his bizarre death. An intricately conceived, diabolical puzzle presented as a collection of texts, including Harriet’s journals, assembled after her death, it tells the tale from multiple perspectives as Harriet’s critics, fans, family, and others offer their own conflicting opinions of where the truth lies.

1. The Blazing World by Siri Hustvedt (2014). This provocative novel about perception, prejudice, desire, and one woman’s struggle to be seen tells the story of artist Harriet Burden, who, after years of having her work ignored, ignites an explosive scandal in New York’s art world when she recruits three young men to present her creations as their own. Yet when the shows succeed and Burden steps forward for her triumphant reveal, she is betrayed by the third man, Rune. Many critics side with him, and Burden and Rune find themselves in a charged and dangerous game, one that ends in his bizarre death. An intricately conceived, diabolical puzzle presented as a collection of texts, including Harriet’s journals, assembled after her death, it tells the tale from multiple perspectives as Harriet’s critics, fans, family, and others offer their own conflicting opinions of where the truth lies.

2. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

2. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

3. Survival in Auschwitz by Primo Levi (1947). In 1943, Primo Levi, a twenty-five-year-old chemist and “Italian citizen of Jewish race,” was arrested by Italian fascists and deported from his native Turin to Auschwitz. This memoir is Levi’s classic account of his ten months in the German death camp, a harrowing story of systematic cruelty and miraculous endurance. Remarkable for its simplicity, restraint, compassion, and even wit, it remains a lasting testament to the indestructibility of the human spirit.

3. Survival in Auschwitz by Primo Levi (1947). In 1943, Primo Levi, a twenty-five-year-old chemist and “Italian citizen of Jewish race,” was arrested by Italian fascists and deported from his native Turin to Auschwitz. This memoir is Levi’s classic account of his ten months in the German death camp, a harrowing story of systematic cruelty and miraculous endurance. Remarkable for its simplicity, restraint, compassion, and even wit, it remains a lasting testament to the indestructibility of the human spirit.

4. The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton (1905). Caught up in the web of old New York society, Lily Bart angles for a wealthy husband. Though presented with ample opportunity, the beautiful and well-connected Lily rejects one man after another as not rich enough, including her true love, Laurence Stern. When she becomes a hapless victim of her own ambition—blackmailed and wrongly accused of adultery—Lily is cast out of high society before making one final attempt to redeem herself.

4. The House of Mirth by Edith Wharton (1905). Caught up in the web of old New York society, Lily Bart angles for a wealthy husband. Though presented with ample opportunity, the beautiful and well-connected Lily rejects one man after another as not rich enough, including her true love, Laurence Stern. When she becomes a hapless victim of her own ambition—blackmailed and wrongly accused of adultery—Lily is cast out of high society before making one final attempt to redeem herself.

5. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847). Like Wuthering Heights, this is a romance set in the isolated moors of rural England the Brontës called home. Its title character is an exceptionally independent orphan who becomes governess to the children of an appealing but troubled character, Mr. Rochester. As their love develops, the author introduces a host of memorable characters and a shattering secret before sending Jane on yet another arduous journey.

5. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847). Like Wuthering Heights, this is a romance set in the isolated moors of rural England the Brontës called home. Its title character is an exceptionally independent orphan who becomes governess to the children of an appealing but troubled character, Mr. Rochester. As their love develops, the author introduces a host of memorable characters and a shattering secret before sending Jane on yet another arduous journey.

6. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

6. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky (1866). In the peak heat of a St. Petersburg summer, an erstwhile university student, Raskolnikov, commits literature’s most famous fictional crime, bludgeoning a pawnbroker and her sister with an axe. What follows is a psychological chess match between Raskolnikov and a wily detective that moves toward a form of redemption for our antihero. Relentlessly philosophical and psychological, Crime and Punishment tackles freedom and strength, suffering and madness, illness and fate, and the pressures of the modern urban world on the soul, while asking if “great men” have license to forge their own moral codes.

7. The Picture of Dorian Grey by Oscar Wilde (1891). Wilde’s only novel offers a devastating portrait of the effects of evil and debauchery on a young aesthete in late-19th-century England. Combining elements of the Gothic horror novel and decadent French fiction, the book centers on a striking premise: As Dorian Gray sinks into a life of crime and gross sensuality, his body retains perfect youth and vigor while his recently painted portrait grows day by day into a hideous record of evil, which he must keep hidden from the world. First published as a serial story in the July 1890 issue of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, the editors feared the story was indecent, and without Wilde's knowledge, deleted five hundred words before publication. Despite that censorship, it offended the moral sensibilities of British book reviewers, some of whom said that Oscar Wilde merited prosecution for violating the laws guarding the public morality.

7. The Picture of Dorian Grey by Oscar Wilde (1891). Wilde’s only novel offers a devastating portrait of the effects of evil and debauchery on a young aesthete in late-19th-century England. Combining elements of the Gothic horror novel and decadent French fiction, the book centers on a striking premise: As Dorian Gray sinks into a life of crime and gross sensuality, his body retains perfect youth and vigor while his recently painted portrait grows day by day into a hideous record of evil, which he must keep hidden from the world. First published as a serial story in the July 1890 issue of Lippincott's Monthly Magazine, the editors feared the story was indecent, and without Wilde's knowledge, deleted five hundred words before publication. Despite that censorship, it offended the moral sensibilities of British book reviewers, some of whom said that Oscar Wilde merited prosecution for violating the laws guarding the public morality.

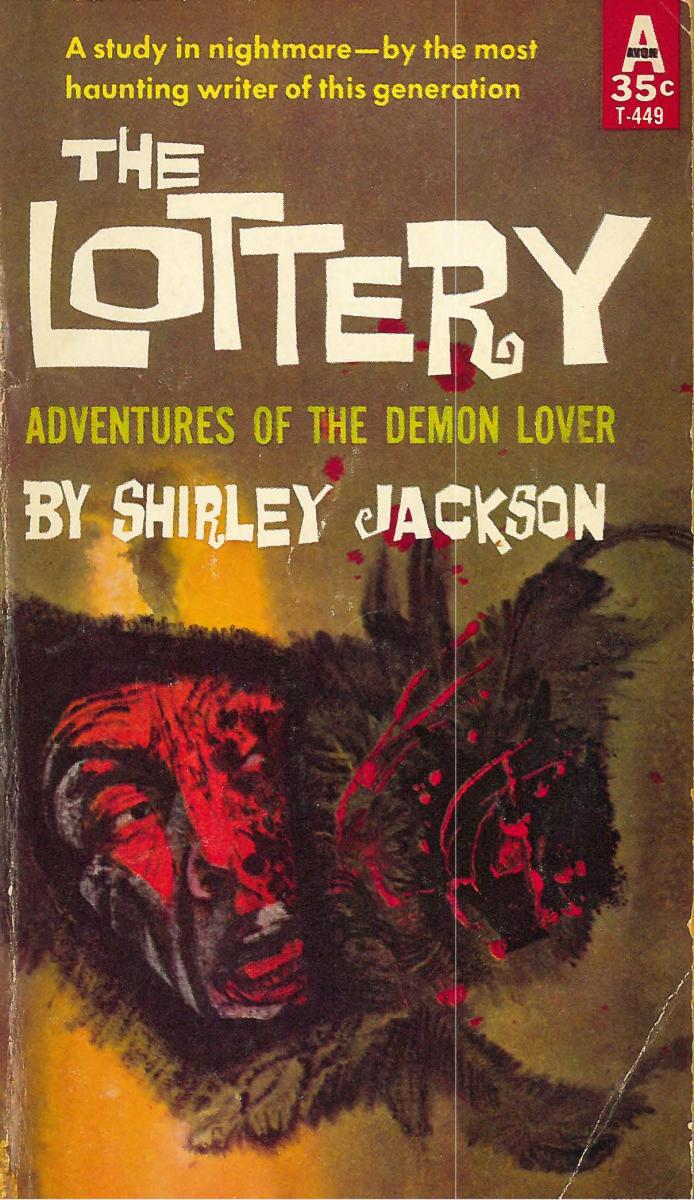

8. The Lottery and Other Stories by Shirley Jackson (1916-65). From the early 1940s through the mid-1960s, Jackson wittily remade the genre of psychological horror for an alienated, postwar America. The title story, one of the most anthologized stories in American fiction, explores the idea of conformity through a small village that sacrifices one of its citizens each year (the lottery “winner!”) to ensure a good harvest. The collection also includes the disturbing and mysterious "The Daemon Lover,"; "Charles," the hilarious sketch that launched Jackson's secondary career as a domestic humorist. Here too are Jackson's masterly short novels: "The Haunting of Hill House" (1959), the tale of an achingly empathetic young woman chosen by a haunted house to be its new tenant, and "We Have Always Lived in the Castle" (1962), the unrepentant confessions of Miss Merricat Blackwood, a cunning adolescent who has gone to quite unusual lengths to preserve her ideal of family happiness.

8. The Lottery and Other Stories by Shirley Jackson (1916-65). From the early 1940s through the mid-1960s, Jackson wittily remade the genre of psychological horror for an alienated, postwar America. The title story, one of the most anthologized stories in American fiction, explores the idea of conformity through a small village that sacrifices one of its citizens each year (the lottery “winner!”) to ensure a good harvest. The collection also includes the disturbing and mysterious "The Daemon Lover,"; "Charles," the hilarious sketch that launched Jackson's secondary career as a domestic humorist. Here too are Jackson's masterly short novels: "The Haunting of Hill House" (1959), the tale of an achingly empathetic young woman chosen by a haunted house to be its new tenant, and "We Have Always Lived in the Castle" (1962), the unrepentant confessions of Miss Merricat Blackwood, a cunning adolescent who has gone to quite unusual lengths to preserve her ideal of family happiness.

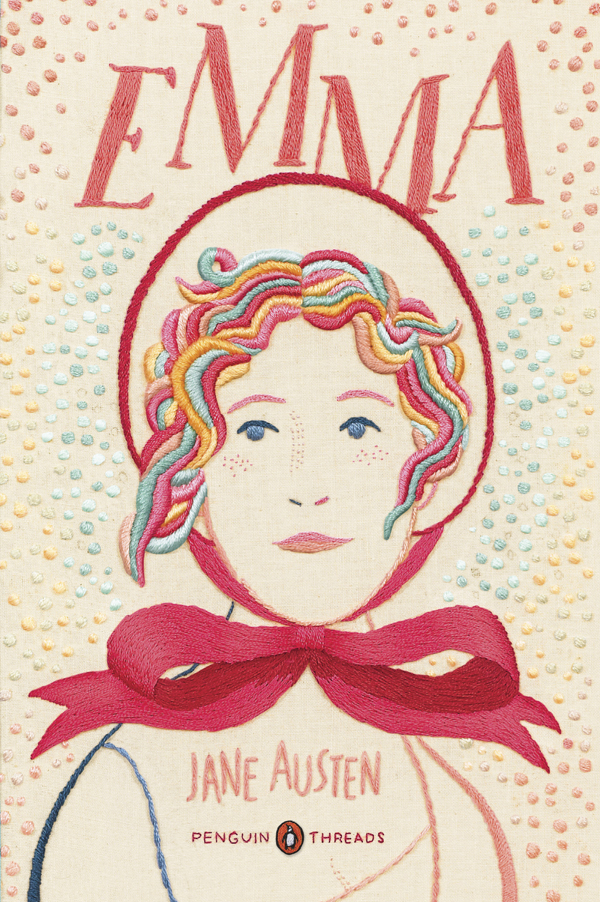

9. Emma by Jane Austen (1816). The story of Miss Woodhouse—busybody, know-it-all, and general relationship enthusiast—is a comedy of manners deftly laced with social criticism. The charm largely inheres in Emma’s imperfections: her slightly spoiled maneuverings, her highly fallible matchmaking, her inability to know her own heart. Emma teeters from lovable one moment to tiresome and self-centered the next. In writing her story, Austen found an ideal venue for her note-perfect, never-equaled archness.

9. Emma by Jane Austen (1816). The story of Miss Woodhouse—busybody, know-it-all, and general relationship enthusiast—is a comedy of manners deftly laced with social criticism. The charm largely inheres in Emma’s imperfections: her slightly spoiled maneuverings, her highly fallible matchmaking, her inability to know her own heart. Emma teeters from lovable one moment to tiresome and self-centered the next. In writing her story, Austen found an ideal venue for her note-perfect, never-equaled archness.

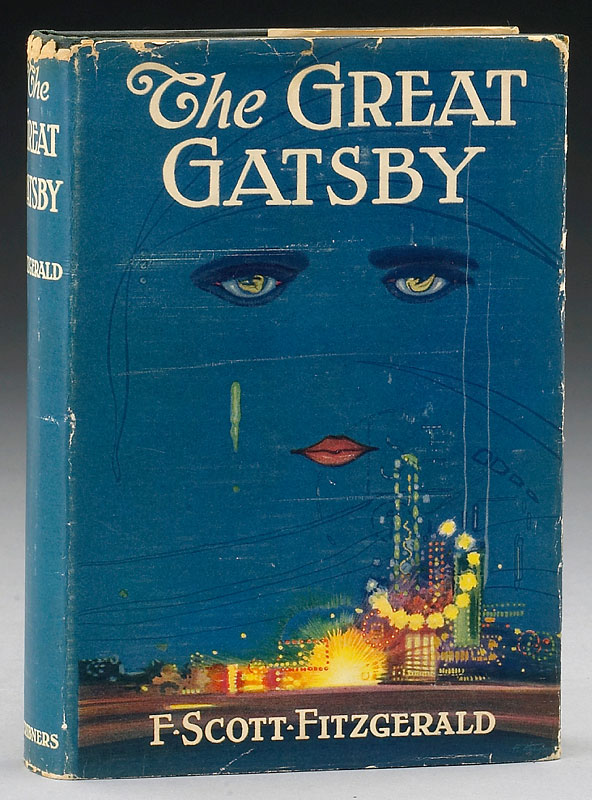

10. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925). Perhaps the most searching fable of the American Dream ever written, this glittering novel of the Jazz Age paints an unforgettable portrait of its day— the flappers, the bootleg gin, the careless, giddy wealth. Self-made millionaire Jay Gatsby, determined to win back the heart of the girl he loved and lost, emerges as an emblem for romantic yearning, and the novel’s narrator, Nick Carroway, brilliantly illuminates the post–World War I end to American innocence.

10. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925). Perhaps the most searching fable of the American Dream ever written, this glittering novel of the Jazz Age paints an unforgettable portrait of its day— the flappers, the bootleg gin, the careless, giddy wealth. Self-made millionaire Jay Gatsby, determined to win back the heart of the girl he loved and lost, emerges as an emblem for romantic yearning, and the novel’s narrator, Nick Carroway, brilliantly illuminates the post–World War I end to American innocence.