Author Photo And Bio

1. Labyrinths by Jorge Luis Borges (1964). Simultaneously philosophical and nightmarish, this collection of short stories, parables, and essays popularized both Latin American magic realism as well as metafiction. Borges, a blind Argentine librarian and polymath, here provides almost mathematically concise miniatures —of a man who remembers literally everything, for instance —that read like episodes of The Twilight Zone as written by a metaphysician.

1. Labyrinths by Jorge Luis Borges (1964). Simultaneously philosophical and nightmarish, this collection of short stories, parables, and essays popularized both Latin American magic realism as well as metafiction. Borges, a blind Argentine librarian and polymath, here provides almost mathematically concise miniatures —of a man who remembers literally everything, for instance —that read like episodes of The Twilight Zone as written by a metaphysician.

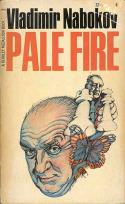

2. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962). “It is the commentator who has the last word,” claims Charles Kinbote in this novel masquerading as literary criticism. The text of the book includes a 999-line poem by the murdered American poet John Shade and a line-by-line commentary by Kinbote, a scholar from the country of Zembla. Nabokov even provides an index to this playful, provocative story of poetry, interpretation, identity, and madness, which is full to bursting with allusions, tricks, and the author’s inimitable wordplay.

2. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov (1962). “It is the commentator who has the last word,” claims Charles Kinbote in this novel masquerading as literary criticism. The text of the book includes a 999-line poem by the murdered American poet John Shade and a line-by-line commentary by Kinbote, a scholar from the country of Zembla. Nabokov even provides an index to this playful, provocative story of poetry, interpretation, identity, and madness, which is full to bursting with allusions, tricks, and the author’s inimitable wordplay.

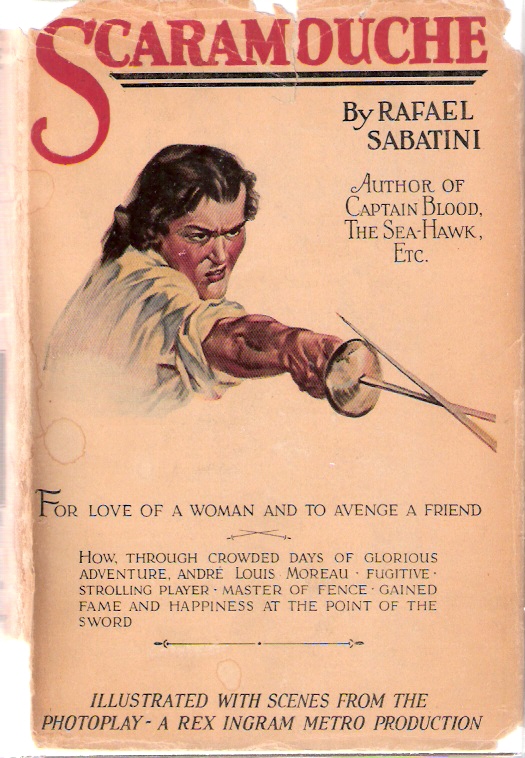

3. Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini (1921). Swashbuckling swordsman, inspiring orator, actor, lawyer, revolutionary politician, Andre-Louis Moreau “was born with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.” He must employ all his skills in seeking revenge against the wicked aristocrat who murdered his friend, a young clergyman, for expressing democratic ideas. The tension mounts when Moreau learns his adversary hopes to wed his beloved. A master of action-adventure (his other works include Captain Blood), Sabatini paints Moreau’s story against the surging French Revolution, coloring his high drama with history and politics.

3. Scaramouche by Rafael Sabatini (1921). Swashbuckling swordsman, inspiring orator, actor, lawyer, revolutionary politician, Andre-Louis Moreau “was born with the gift of laughter and a sense that the world was mad.” He must employ all his skills in seeking revenge against the wicked aristocrat who murdered his friend, a young clergyman, for expressing democratic ideas. The tension mounts when Moreau learns his adversary hopes to wed his beloved. A master of action-adventure (his other works include Captain Blood), Sabatini paints Moreau’s story against the surging French Revolution, coloring his high drama with history and politics.

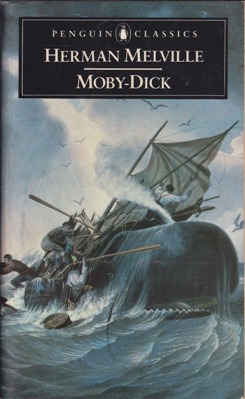

4. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

4. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville (1851). This sweeping saga of obsession, vanity, and vengeance at sea can be read as a harrowing parable, a gripping adventure story, or a semiscientific chronicle of the whaling industry. No matter, the book rewards patient readers with some of fiction’s most memorable characters, from mad Captain Ahab to the titular white whale that crippled him, from the honorable pagan Queequeg to our insightful narrator/surrogate (“Call me”) Ishmael, to that hell-bent vessel itself, the Pequod.

5. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813). “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” reads this novel’s famous opening line. This matching of wife to single man —or good fortune —makes up the plot of perhaps the happiest, smartest romance ever written. Austen’s genius was to make Elizabeth Bennet a reluctant, sometimes crabby equal to her Mr. Darcy, making Pride and Prejudice as much a battle of wits as it is a love story.

5. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813). “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife,” reads this novel’s famous opening line. This matching of wife to single man —or good fortune —makes up the plot of perhaps the happiest, smartest romance ever written. Austen’s genius was to make Elizabeth Bennet a reluctant, sometimes crabby equal to her Mr. Darcy, making Pride and Prejudice as much a battle of wits as it is a love story.

6. Tales of Mystery and Imagination by Edgar Allan Poe (1836–47). These pieces influenced almost every contemporary genre, from adventure stories (“The Narrative of A. Gordon Pym”) to amateur detective mysteries (“The Purloined Letter”) to lurid horror tales (“The Cask of Amontillado”). Poe’s fascination with psychology and the dark sides of human behavior jump-started the first great age of American fiction and, through his influence on French symbolists such as Baudelaire, helped to transform literature in the nineteenth century.

7. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

7. In Search of Lost Time by Marcel Proust (1913–27). It’s about time. No, really. This seven-volume, three-thousand-page work is only superficially a mordant critique of French (mostly high) society in the belle époque. Both as author and as “Marcel,” the first-person narrator whose childhood memories are evoked by a crumbling madeleine cookie, Proust asks some of the same questions Einstein did about our notions of time and memory. As we follow the affairs, the badinage, and the betrayals of dozens of characters over the years, time is the highway and memory the driver.

8. Paradise Lost by John Milton (1667). Recasting the biblical story of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace, this epic poem details Satan’s origins, his desire for revenge, his transformation into the serpent, and his seduction of Eve. The poem extends our understanding of Christian myth in lush and challenging language. Though Milton seeks to explain “the ways of God to man,” he gives Satan — “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven” — the best lines.

8. Paradise Lost by John Milton (1667). Recasting the biblical story of Adam and Eve’s fall from grace, this epic poem details Satan’s origins, his desire for revenge, his transformation into the serpent, and his seduction of Eve. The poem extends our understanding of Christian myth in lush and challenging language. Though Milton seeks to explain “the ways of God to man,” he gives Satan — “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven” — the best lines.

9. Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez (1985). Márquez takes the love triangle to the limit in this story of an ever hopeful romantic who waits more than fifty years for his first love. When his beloved’s husband dies after a long, happy marriage, Florentino Ariza immediately redeclares his passion. After the enraged widow rejects him, he redoubles his efforts. Set on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, this wise, steamy, and playful novel jumps between past and present, encompassing decades of unrest and war, recurring cholera epidemics, and the environmental ravages of development.

9. Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez (1985). Márquez takes the love triangle to the limit in this story of an ever hopeful romantic who waits more than fifty years for his first love. When his beloved’s husband dies after a long, happy marriage, Florentino Ariza immediately redeclares his passion. After the enraged widow rejects him, he redoubles his efforts. Set on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, this wise, steamy, and playful novel jumps between past and present, encompassing decades of unrest and war, recurring cholera epidemics, and the environmental ravages of development.

10. The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler (1953). Chandler’s sardonic and chivalric gumshoe Philip Marlowe winds up in jail when he refuses to betray a client to the Los Angeles police investigating the murder of a wealthy woman. Marlowe’s incorruptibility and concentration on the case are challenged even more when the obsessively independent private eye falls in love, apparently for the first time, with a different rich and sexy woman. She proposes marriage, but he puts her off, claiming he feels “like a pearl onion on a banana split” among her set.

10. The Long Goodbye by Raymond Chandler (1953). Chandler’s sardonic and chivalric gumshoe Philip Marlowe winds up in jail when he refuses to betray a client to the Los Angeles police investigating the murder of a wealthy woman. Marlowe’s incorruptibility and concentration on the case are challenged even more when the obsessively independent private eye falls in love, apparently for the first time, with a different rich and sexy woman. She proposes marriage, but he puts her off, claiming he feels “like a pearl onion on a banana split” among her set.